Bruno in his usual afternoon spot. Like a number of the residents of Certaldo Alto, he lives in the house he was born in. His daughter lives near, as does his grandson, my electrician.

Bruno

Stories. God, I love them. The courage of people—everyday people that you see on the street. Our determination not just to survive but to thrive with grace and humor. We are an amazing species.

This is Bruno Signorini. Every afternoon, Bruno’s daughter pushes his wheelchair down the street so he can sit with a group of older people who congregate to visit and watch the tourists.

Bruno doesn’t talk much. But he has a very expressive face and gentle, big brown eyes. He’s always wearing an immaculate shirt, often in a gingham print, the white checks so bright they glow. If you ask him how he is, he always answers, “Contento.” I am content.

But one day, Bruno began to talk. I’m not sure how it all started, but he started talking to me in Italian. His daughter translated. Bruno told me about being drafted into the Italian army during WWII, when he was eighteen years old. Two years later, when Italy broke away

from the Nazis, Bruno was among the 710,000 Italian military POWs transported as forced labor to Germany. That’s a statistic. An old one at that. It conveys almost nothing to us. Tomorrow, Bruno promised me, he would bring things to show me.

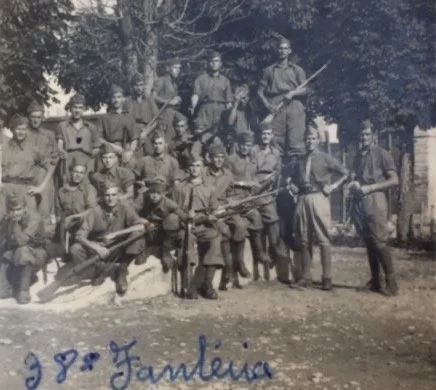

A lot of pictures like this in picture boxes around the world. I think Bruno is the one on the back left with the ink dot on his chest.

I made sure I didn’t miss that appointment. Sure enough, Bruno had a little plastic bag. Out came a metal dog tag on a twine cord. Stalag III A. Here was his identification card issued by the POW camp consisting of a metal-framed picture of him as a young man. Here was an official passport-type document, a swastika on the front, showing to which camp he was assigned, with pages for them to note if they moved him. There were a few pictures from before he was interred, pictures of him with his Italian mates. They could have been young American soldiers but for the uniforms.

Bruno’s dog tag

There were a few letters back and forth between Bruno and his mother. She was allowed to send two packages each year. He thanked her for the food, but reminded her that it had to travel a long way and that many things wouldn’t keep, so she shouldn’t send fruit. But the figs made it, and they were delicious. He asked her to send flour and yellow flour (corn meal) because they had nothing to eat but the greens they foraged.

Bruno’s mother saved his letters as he did hers, and now they are united in his plastic bag along with the other articles from a long-gone past. But I think Bruno’s suffering softened him into a kind soul. The look in his eyes now is nothing like the one on the face of the young Italian soldier. Bruno appreciates life and is “contento” to sit in the sun with his friends and be allowed an occasional gelato by his attentive daughter.

Letters to Mom, the I.D. card, and the inside of the identity document.

Stories like Bruno’s are all around us all over the world, and their value cannot be overestimated. Not only do they connect us across continents to those who at one time were considered the “enemy,” but, just as importantly, they connect us across generations.

How the Nazis kept up with their vast number of prisoners.

The threads of a person's story, like little wildflower roots, reach into our hearts. Like Bruno’s letters to his mom about flour. Like his “contento” reply.

Stories lift us, connect us, remind us how our fragile lives are intertwined under the surface like a field of wildflowers. Stories remind us that none of us are “ordinary,” that all of us carry a burden, that each of us is unique, and yet, so much the same.

I am humbled and honored that on a summer day in Tuscany, a stranger I hardly knew chose to share his story with me.